The Boys Need Their Candies: The Trial of Vince McMahon and the WWF, Part 1

On the 25th anniversary of the start of Vince McMahon's federal trial on charges of conspiring to distribute steroids and defraud the FDA, a free preview of an ongoing series.

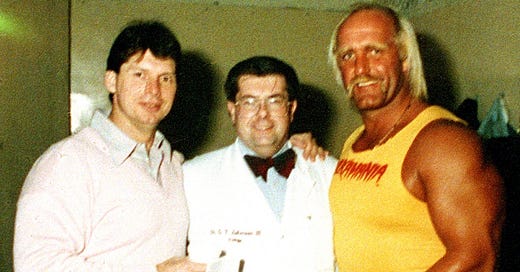

Photo: Vince McMahon, Dr. George Zahorian, and Hulk Hogan. (Produced to news outlets by Zahorian in 1991)

As promised, it’s here. Titled The Boys Need Their Candies, Babyface v. Heel will be taking an ongoing look at the steroid scandal and resulting federal criminal trials that rocked World Wrestling Entertainment, then Titan Sports d/b/a the World Wrestling Federation, in the early 1990s. Drawing on the full transcripts of both trials (Dr. George Zahorian in 1991 and Vince McMahon/Titan Sports in 1994), court filings, FBI case notes, and other primary sources, as well as other historical records, this is going to be the most in-depth account of the cases ever written, and will include details never-before reported.

The Boys Need Their Candies starts with a look at how the cases fell into place; this entry is being made available for free. Starting next week, after the close of Independence Day weekend, you will need to become a paid subscriber for $5/month or $50/year to be able to have full access to subsequent entries in this series. If you enjoy this, please support it, because I promise you that you will not be disappointed with the reporting in The Boys Need Their Candies or the other content to come at Babyface v. Heel.

Thank you, and enjoy the weekend,

David Bixenspan

In the Spring of 1987, Titan Sports, the parent company of the World Wrestling Federation, was on top of the world. Just nine days after the March equinox, President & CEO Vincent Kennedy McMahon’s company had promoted the biggest event in the history of professional wrestling, WrestleMania III. Packing tens of thousands of screaming fans into a sold-out Pontiac Silverdome, drawing 450,000 fans across North America who left their homes to watch the show on closed-circuit television, and generating 400,000 pay-per-view orders, it was the most unmitigated possible success. The main event of Hulk Hogan vs. Andre the Giant was the right match in the right place at the right time, with the live crowd at a fever pitch for the opening stare down. As the two huge and hugely famous men faced off, play-by-play announcer Gorilla Monsoon bellowed out one of his favorite cliches: “The irresistible force meets the immovable object!”

Less than three months later, as the season was about to come to a close, Monsoon and Titan found themselves in a different kind of fight. Under his real name of Robert Marella, Gorilla had long worked in the WWF office, and on the morning of June 11th, he found himself flanking his boss, Titan Sports Executive Vice President Linda McMahon, as she embarked on a trip to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania with lawyers Rick Santorum—the future U.S. Senator—and Jack Krill. There, Gorilla would lend some star power as she testified in front of an ad-hoc committee of the state House of Representatives. The legislative body was evaluating the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission, after a sunset review painted a less than flattering picture of the agency that oversaw the curious mix of boxing, amateur wrestling, and the entertainment sport that is professional wrestling. Titan had been lobbying for the commission’s regulation of their business to be abolished, but that was easier said than done, especially since an audit of the commission leaned towards smaller changes.

“Without state regulatory involvement, there would be few controls to prevent promoters or wrestlers from becoming overzealous in their pursuit to obtain an audience for their shows,” reads the audit. “For example, the auditors were informed of and have seen evidence of abuses perpetrated by profession al wrestlers, including the drawing of blood by self-inflicted wounds (spe cifically, cutting one's forehead with a razor blade).” Concerns over mandating crowd control and unscrupulous promoters were also cited…was the license fee pro wrestling representing over 80% of commission revenue in the previous two calendar years. Money was at the heart of the matter, but it wasn’t everything, as the commission being a nuisance was also at issue.

The beginning of the transcript of Linda’s McMahon’s appearance before the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

“I think the one other thing that is really almost more important to our event itself, our event comes as a package,” McMahon explained before the House. “We have our announcers, we have our referees, we have our timekeepers. We have everything that is necessary for our event. For the state to appoint to our form of entertainment an announcer who cannot pronounce the names of our wrestlers, or a referee who is not necessarily part of our event, and may not act accordingly in the ring for our particular kind of performance, a timekeeper who, I don't know why we have to have him and pay him anyway. That is $40 to $50 every night just for a timekeeper. Those are the things that are really impediments to our performance.” Perhaps more importantly, she also noted that at least in her company, the important things, like having a doctor in attendance, were already being handled privately. Besides, like the report said, the commissioners and promoters professed to have no knowledge “of any deaths or serious injuries having occurred during a professional wrestling match.”

PSAC Chairman James J. “J.J.” Binns was strongly in favor of maintaining the status quo, just changing the controls, with a particular concern for stopping wrestlers from “blading”—cutting themselves with small pieces of razors—to bleed in the ring. At least in the moment, he didn’t get his way, as the House voted to kill the commission outright. That didn’t go much further, but Titan’s lobbying did. Two years later, the Professional Wrestling Act was passed, and while it didn’t eliminate the commission’s wrestling oversight altogether, it loosened the reigns a bit. Among other things, the promoter and building owner were made responsible for security, self-mutilating by wrestlers was banned, boxing-oriented rules were tweaked to exempt pro wrestling, and the promoter would hire the ringside doctor “from a list approved by the Department of Health.”

That last one would be key.

For a decade, the preferred commission-appointed physician at WWF shows was Dr. George T. Zahorian III, an osteopath specializing in urology who had an obvious sense of hero worship for the performers. “I could not believe that I was sitting in an exam room or sitting at the ring of individuals that I had admired for years at home and examining these men and being able to talk to them and actually know that they were human beings, that these men were doing a job,” he would explain while testifying on his own behalf in 1991. “The amazing thing that I didn't know when I was growing up was what type of job these men were doing, what the entertainment was, but also that these men were human and these men did hurt and these men did get hurt. And it was amazing what they could go through.”

Zahorian was enraptured by the wrestlers, and, to hear him tell it, they came to see him as not just a familiar, educated expert to confide in, but a friend as well. So much so that, when his own defense lawyer showed him pictures of himself and his family with various wrestling stars, he got emotional. “Excuse me, over the years these individuals were more than my patients,” he testified. “I considered these men part of my family. They were so misunderstood. People would make fun of these men. People would look at them as freaks, men from side shows. These individuals were human beings. These individuals lived. They breathed. They had a job to do and their job was entertainment. They had nobody to go to to talk to. I loved those men and to this day I love those men because as the years went on I was able to find out what these men were doing.”

Wait, what exactly were they doing?

“These men came in and talked to me, and after about a year, two years they opened up their hearts to me,” Zahorian explained. “They would come in with some of the medications that they are taking...the anabolic steroids” This was already a risky enough path, and sure enough, one day in 1982, there was a particular conversation that he recalled with an unnamed wrestler that would change his life.

“One man came in to me, showed me a bottle, ‘Doc, can you get this for me?’” he recalled. “I looked at the bottle. I read the label. I said, ‘What's that label say?’ ‘For veterinarian use.’ I said, ‘You see your form there, you didn't sign it. Sign your form.’ He puts an ‘X.’ I said, ‘Can you write?’ He says, ‘No.’ I said, ‘Can you read?’ He says, ‘No.’ ‘Do you know that that said for veterinarian use? Where did you get that?’” Wanting to “educate” the wrestlers, he started to give them more attention, considered them his patients, and started to sell steroids and other drugs—generally opioid painkillers and other assorted downers—to them. And as much as he tried to frame the relationship as a legitimate doctor/patient arrangement and not that of a drug dealer and his client, his testimony three years after his own trial, during the trial of Vince McMahon and Titan Sports, indicates otherwise.

“If a wrestler requested the anabolic steroids, or [codeine-based] Tylenol number Three, or Tylenol number Four, at that point I would give them those drugs,” he testified in 1994. Asked by prosecutor Sean O’Shea if “you gave them whatever they requested,” Zahorian replied “Yes;” he later conceded that, in O’Shea’s words, he was not “acting properly as a physician.” Then again, anyone in the locker room could have told you that. “I was lined up waiting for Dr. Zahorian again,” wrote Bret “Hitman” Hart of September 8, 1985 in his memoir Hitman. “One by one I watched damn near everybody come out of Zahorian’s room with grocery bags full of drugs, even Vince. It often happened that wrestlers bought so many drugs that they couldn’t carry them in their suitcases and had to ship them home. No one heeded the warning signs, though I tried really hard to be moderate. ”

Less than eight weeks later, “Quick Draw” Rick McGraw, a WWF wrestler who was one of Zahorian’s most prolific customers, died from a heart attack at just 30 years of age. His death on Friday, November 1st, came far too late in the distribution process for the weekend’s WWF programming to be edited to reflect his passing. With his last television match being an unusually brutal and one-sided loss to “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, an infamous urban legend sprouted up amongst some of the more naive wrestling fans that McGraw died of injuries sustained in that bout. Even with The Associated Press wire running a national item on his death stating that “an autopsy…revealed no signs of injury or foul play,” that was in the air for years. And it had the strange side effect of obscuring why a 30 year old athlete and semi-featured television performer had died suddenly.

At the start of the year, on January 10th, in Hershey, Pennsylvania, while Hart waited in line to see the good doctor himself, he was taken aback to see his peer’s haul. “Quick Draw came out of Zahorian’s room carrying his own personal pharmacy: vials of steroids and an assortment of small boxes containing Valium, Percocet, Halcion, speed and his much loved Placidyls,” Hart wrote. “He could have used a grocery cart.” When it was Hart’s turn, his description of his first transaction with Zahorian does not exactly evoke the beginning of a close doctor/patient relationship. “When it was my turn, the doctor took my blood pressure and pulse,” recalled Hart. “Then, like everyone else in the line, I handed him some crisp hundred-dollar bills and stocked up on twenty vials of testosterone, twenty Deca-Durabolin and four bottles of gonadotropin—to keep my balls from shrinking—along with several boxes of Halcion so I could sleep and a cache of needles.”

This went on for years, and with the WWF constantly in Pennsylvania, there were plenty of opportunities for the wrestlers to get their drugs: Through June 1984, the company would do back-to-back television tapings in Allentown and Hamburg every three weeks. Even after that stopped, it didn’t impede Zahorian’s side business much; in 1986, the WWF ran 77 shows in the Keystone State in the calendar year. On top of that, Zahorian began shipping steroids to wrestlers via Federal Express, creating a paper trail that would help lead to his eventual undoing. At one point in early 1988, as Zahorian testified to six years later, Vince McMahon expressed concern about the origin of some of the drugs, but seemed satisfied with the doctor explaining that he got them from legitimate pharmacies. “I was concerned as to what these men were taking,” the doctor recalled. “But I again told him that if you do not want me to do this, I will stop. He in turn said, ‘No, that's okay. You continue what you are doing.’” This whole arrangement, though, was upended by 1989’s Professional Wrestling Act requiring wrestling promoters to hire the ringside doctors themselves.

A portion of the court reporter’s transcript of Anita Scales’s 1994 trial testimony.

Anita Scales, Titan’s then-Director of Compliance and Regulations, was the individual who that specific duty fell to. And as she testified in 1994, this new wrinkle was actually her company’s doing. “Titan Sports hired people to assist in the writing of the portions of the bill or lobbying that would have affected our business,” she explained. Needing to fill spots quickly because the new regulations went into effect immediately, she called the arenas for recommendations, but had no desire to retain Zahorian. Why? “Because I had heard rumors about him dating back to when I was working in Greenwich.” A month later, he started trying to get back in the loop. “He made a number of calls,” she testified. “I got very irritated and started to document them.” Zahorian was insistent that Hershey was “his” town, but Scales was having none of it.

So the doctor went above her head.

Pat Patterson, Titan’s Senior Vice President of Wrestling Operations, called Scales several weeks later, asking for Zahorian to be assigned to Hershey because “the boys wanted him.” That was followed shortly by road agent/backstage producer Jay “Chief Jay Strongbow” Scarpa—also the father of then-WWF wrestler Mark Young—ringing her up and requesting same. “By this time I was getting very annoyed because I got other calls from Zahorian's office,” recalled Scales. “And I said, no, I didn't want to assign him.” Scarpa, she testified, responded with a bluntness you might not expect in a conversation with the “corporate” non-wrestling side of the company.

“He said the boys need their candies…I said they could get their damn candies somewhere else.”

Scales consulted with two people on the wrestling side who she felt would give her a reasonable assessment of the situation, Gorilla Monsoon and road agent Tony Garea. Both, she said, were anti-Zahorian, classifying him as “sleazy,” with Monsoon adding that “there was no room in the business for people like that.” Gorilla also didn’t give her any real advice. “He said, ‘Well, kid, I guess you are between a rock and a hard place.’ And that was pretty much the end of the conversation.” She stuck to her guns, but when the Hershey event in question came around in October, Scales got a confused call from agent Bob “Rene Goulet” Bedard. “[He] was the secondary agent that evening, the evening before at Hershey, and had to pay the physician,” she said. “And he wondered why there had been two there. And I said ‘I only assigned one. Who was the other one?' He said, ‘Well, Dr. Zahorian was there.’” He showed up in an unofficial capacity, later testifying in 1994 that Patterson and road agent Arnold Skaaland asked him to show up, albeit only in the locker room and not before the fans as ringside doctor.

Having “realized that there was a powerlessness,” she went to see her direct supervisor, Linda McMahon. “I explained to her I was receiving pressure from within the company to assign Dr. Zahorian to Hershey,” she said. “And I had believed with the law change that it was my responsibility to make the choice. And we had carefully researched physicians in Pennsylvania, and that this should be my choice, and I was being asked to assign Dr. Zahorian […] I said, Pat wants him assigned, and I heard scurrilous things, and I don't want him here. And she said, ‘you do what Pat says.’”

And that’s what Scales did.

The opening of the telltale memo.

The next time the issue came up, it was in the form of a call from Elizabeth DiFabio, Linda’s executive assistant. That Hershey show was going to be December 26th, and someone “political in nature, from a lobbyist, or a law firm, or a political office” having placed a call about taking their kids backstage to meet the wrestlers as a Christmas present, Scales was now being told that Zahorian could not be used in Hershey, “I said, ‘Well, you wanted him there.’ She says, ‘Well, he can't be there.’ So, I said, ‘I will take care of it.’”

She marched down the hall to Patterson’s office.

“I said, ‘You heard about Dr. Zahorian?’ He said, ‘yes.’ And I said, ‘Well, you wanted him there. You get rid of him. I will get his replacement.’” On December 4th, she notified the commission of the change, and that was that. But what Scales was told wasn’t exactly the whole story, to say the least. A better approximation of that came three days earlier in a memo from her boss to Patterson:

CONFIDENTIAL INTEROFFICE MEMORANDUM

TO: Pat Patterson

FROM: Linda McMahon

DATE: December 1, 1989

RE: Dr. Zahorian

I spoke to Vince about the fact that the State of Pennsylvania is probably going to launch an investigation into the use of all illegal drugs including steroids. An officer from the State Department mentioned to Jack Krill, one of our attorneys, at a recent fundraiser that his office would be conducting these investigations at the same time he told Krill that perhaps it was a bad idea to mention it to him because Krill's firm represents the WWF. In addition, this fellow mentioned that he was aware of Dr. Zahorian and his relationship with the WWF.

Although you and I discussed before about continuing to have Zahorian at our events as the doctor on call, I think that is now not a good idea. Vince agreed, and would like for you to call Zahorian to tell him not to come to any more of our events and to also clue him in on any action the the Justice Department is thinking of taking.

On December 26th the State Athletic Commission is having a small meet and greet session with some of our talent, and I would definitely not want Zahorian there.

Please be in touch with me and I'll relay all the details to you.

Patterson did, indeed, call Zahorian. “I just warned him there was an investigation,” Patterson testified in 1994. “I didn't tell him about steroids or anything else.” Zahorian, for his part, gave significantly more detail.

“He had asked if I was calling from my office,” the urologist testified. “I told him I was. He stated he wanted me to call him from a pay phone. I returned to the hospital, called him from the hospital pay phone. And during that phone conversation he had told me that there was an investigation going on of Titan Sports; that representatives from Titan Sports had been in Washington, D.C. for part of this for some type of a meeting, and at that meeting it was made known to them of the investigation of Titan Sports, and that my name was brought up that I was being investigated. Because of this investigation, that he and Mr. McMahon felt that it was necessary for me to find all information that I had in my presence pertaining to the wrestlers, whether it be their records, telephone numbers, addresses, and destroy this information immediately. They did not want me to have any records whatsoever of the records. And I was very concerned about this. He said that this may be something that is very minor, but we better be careful. And I told him okay. He then said, ‘Look, once this is over, then we will get together and then we can continue with our relationship.’ And that was the end of the conversation with him.”

Less than five years later, on July 20, 1994, that phone call would become key in a conspiracy—between Zahorian and defendants Titan Sports and Vince McMahon—that federal prosecutor Sean O’Shea tried to sell to a jury in Uniondale, New York.

“Think about it, ladies and gentlemen, when was the last time you called your family doctor and said, listen, where are you?” O’Shea asked the jury rhetorically during his closing argument. “You are in your doctor's office? Well, you better go to a pay phone and call me back? When was the last time you did that with a real doctor? That's how drug dealers talk, ladies and gentlemen. That's how drug dealers talk when they want to avoid calling the police, when the police are closing in and maybe somebody is listening in on the telephone.”

But there’s a lot more to get to first, isn’t there?

Did you like the first part of The Boys Need Their Candies? Do you want to keep reading the subsequent chapters that will be published here? Then you need to become a paid subscriber to Babyface v. Heel for just $5/month or $50/year to make sure you don’t miss the next installment of The Boys Need Their Candies and other members-only content.