Why do sexual misconduct allegations manifest differently in pro wrestling?

It keeps coming up, but there's been little analysis of it.

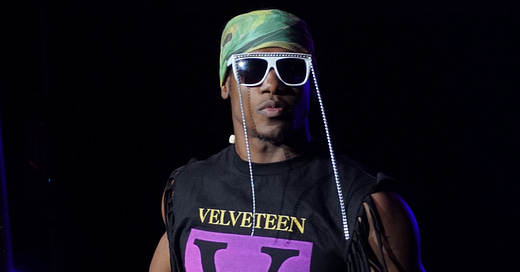

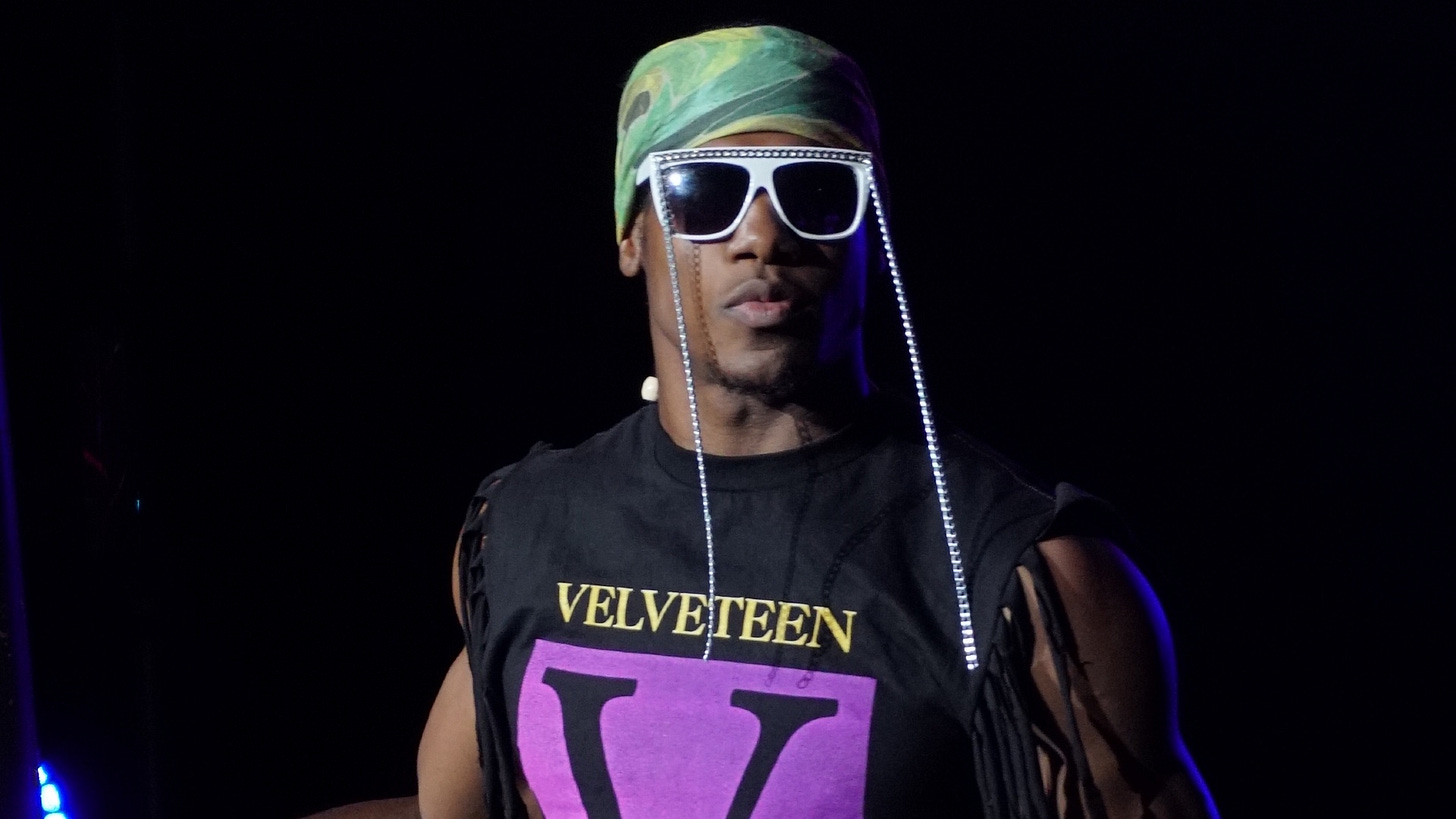

Last night, on POST Wrestling’s REWIND-A-RAW podcast with John Pollock and Wai Ting, they discussed Patrick “Velveteen Dream” Clark’s Instagram Story statement on his sexual misconduct allegations as the lead story of the day. Near the end of the discussion, Pollock raised the issue of the form that the vast majority of allegations of sexual, physical, and emotional abuse have taken in pro wrestling in the last year or so, especially since the #SpeakingOut movement happened last June.

“A larger issue about all of these stories is…how are they to be adjudicated?” he said. “It’s essentially [that] these companies are left to kind of be the arbitrator , and the audience is kind of what they’re going by, like ‘Who are we comfortable using or not using?’ These are not typically…we’re not seeing law enforcement get involved, so it just becomes, essentially, like these stories are just getting played out online and you’re left to draw your own conclusions, when there’s a lot of missing pieces I don’t think the public is equipped to…adjudicate these cases. Because there’s too many questions.”

I would hope everyone can understand the point that he was trying to make; the fact that he hasn’t gotten any blowback I’ve seen suggests that, thankfully, this is the case. This is not John—who, on a day to day basis, covered the #SpeakingOut movement as well as anyone—straying from a “believe victims”/“trust, but investigate” point of view. It’s him being a realist about the fact that, even before #SpeakingOut, but most certainly after, the default for allegations of sexual misconduct and other abuse in the wrestling business has become accusations that are first levied on social media. It’s not exactly a secret that this is not the norm when it comes to accusations against public figures, whose misconduct in the #MeToo era has largely been outed by investigative reporters at major mainstream news organizations, but there’s been little discussion of why that is.

(I’m going to assume you’re familiar with why not going to law enforcement, delays in reporting, etc. are common responses to sexual violence and intimate partner violence more broadly. It’s a pretty universal truth that doesn’t just apply to the wrestling business. Let’s just leave it at that.)

Conversations I’ve had with people—mostly women—in the wrestling business about this, as well as some other reporters, generally point towards a few interconnected factors:

Few wrestling reporters have the training, experience, and/or obvious empathy required to do in-depth reporting on topics like sexual assault, and barely any of the reporters on the wrestling beat period are women.

Mainstream media just generally isn’t going to put the magnifying glass on serious wrestling-related stories using their in-house investigative resources.

When a staff reporter at a mainstream legacy publication actually does contact wrestlers with the goal of investigating a bigger name, even if the reporter is a woman and/or has notable experience covering sexual misconduct, their lack of wrestling knowledge makes it hard for wrestlers to trust the reporter.

Indie wrestlers, promoters, and support staff are going to be a lot less likely to get such scrutiny regardless because of their relative lack of fame.

Even if someone has the skills, contacts, and empathy to get accusers on board, do they have the institutional support that would be needed as far as fact checking, legal review, and legal support in case of threats from the accused? Probably not.

(One more that’s not so intertwined with the others: The COVID-19 pandemic and thus the relative lack of worry about how other wrestlers would react at that weekend’s bookings almost surely helped #SpeakingOut grow to the degree it did.)

Put this all together and it’s entirely understandable why #SpeakingOut played out exactly the way it did. But without fixing these issues, which is a major uphill battle, there’s little room for change.

To give one example—which I have to keep vague for obvious reasons—that illustrates how these problems can manifest: Last year, during #SpeakingOut, one wrestler suggested some women I should talk to about a allegations against specific wrestler whose name was coming up publicly. (The wrestler who was named did not come out of #SpeakingOut unscathed regardless of any action I did or didn’t take.) Unsure of just how appropriate it was. I expressed hesitance at cold messaging or cold calling these women—as in without an introduction—as a straight white male reporter. Even now, almost a year later, when, thanks to certain stories, I’ve built up some degree of additional cachet and trust with female wrestlers in reporting this kind of story, I don’t second-guess my response. The wrestler I was talking to seemed to understand the issue just fine, and, in the next few days, it became increasing clear that the accused would have an uphill battle getting booked in the future, regardless.

If my decision hadn’t quickly ended up somewhat moot, I don’t think I would have just stopped there, though. I likely would have reached out to female wrestler friends, various reporters and editors, etc. But would any of that helped eliminate most of the hurdles I mentioned above? Probably not.

(And because I don’t have a good place to put this: I’m not disregarding any of the men who came forward in #SpeakingOut or beforehand to accuse the likes of Clark, Rick Cataldo, and Jonathan Wolf, but the vast, vast majority of those who came forward were women, and the vast, vast majority of the accused were men alleged to be preying on women. As a result, the gender dynamics in play absolutely play a role in who can comfortably reach out to who.)

At the end of the day, what I want—and what everyone else should want—both professionally and on a human level, is for those who are willing to come forward to be able to say that their story has been vetted by a third party. For better or worse, it helps, and unfortunately, not hitting that threshold makes it much harder for a given accusation to be treated as something more credible than a rumor.

I don’t think anyone likes that there are some stories—Impact Wrestling’s questionable sexual harassment investigation from 2019 is an obvious example—where unconfirmed rumors of the specifics are widespread. There are very legitimate ethical reasons why myself and my colleagues can’t report on those specifics. And it’s not a secret that I’ve seen emails from the investigation, because I’ve been able to share very limited details to help with a related story. But the specifics of most of the allegations make it so easy to identify the accuser that, without permission to use their name, that story is unlikely to go anywhere.

What’s needed to at least try to get the ball rolling on this is clear: More resources (financial, legal, and training) for wrestling reporters, more female wrestling reporters, and mainstream reporters being willing to loop in more wrestling-literate people to help them gain the trust of wrestlers. But there’s little reason to expect any of this to change soon, short of launching a campaign to push Substack into paying an advance to a wrestling-oriented newsletter or three. (It could be mine, it could be one that’s aiming to be fully staffed, or other individual-run ones; I’m not being picky.) Then, they could try to approximate the kind of traditional, high level newsroom process that’s needed to solve the bigger problems with reporting on serious misconduct wrestling.

But if none of that happens, then social media allegations will continue to be the status quo in the wrestling business.